A Tuck in Time

by Cate Murway

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

George Santayana [1863 – 1952] philosopher, essayist, poet and novelist.

"Holocaust" is a word of Greek origin meaning "sacrifice by fire."

Beginning in March 1942, a wave of mass murder swept across Europe and during the next 11 months 4,500,000 human beings were eliminated.

The atrocities that took place at the hands of the Nazi regime are unfathomable.

The Holocaust was the systematic, bureaucratic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of approximately six million Jews by the Nazi regime and its collaborators.

The Senate designated April 7 through 14, 2013, as “Days of Remembrance of the Victims of the Holocaust” in PA, in the hope that we may strive to overcome prejudice and inhumanity through education, vigilance and resistance. Never again.

The prisoners were physically concentrated in one place and the Nazis called these first camps concentration camps. When the killing ended those who survived were released and came out of hiding.

David Tuck is a survivor of the Holocaust, one of the most significant events of the 20th century. He was born in Poland near the German border and raised by his Orthodox Jewish grandparents, Sybil and Jehuda, after his mother, Pola passed away just six weeks after his birth. “I have a picture of her but I never knew her.”

His “Babbi” and “Zaida” insisted that he receive both a public and Hebrew education.

“Everyone else has a mother and father.” His grandmother answered him, “You have me.”

David met his father, Morris and his step-mother, Luba and his step siblings, Karola, Fela and Ben for the first time when he was eight years old and lived with them for only 2 years.

When WWII broke out, his family was deported to the Łódź ghetto that provided much needed supplies for Nazi Germany and especially for the German Army. He spoke German well enough and was soon sent to Posen, a labor camp, to be a machine mechanic at the age of 15 years old, catapulted into adulthood.

He worked in Eintrachthütte, a sub-camp of Auschwitz, building anti-aircraft guns. The master sergeants were commanders SS-Hauptscharführer Josef Remmele and SS-Hauptscharführer Wilhelm Gehring. The camp consisted of a few wooden barracks for the prisoners [the administration building was brick] and it was double fenced with high-voltage barbed wire. Later, he labored on autobahn projects, the nationally coordinated motorway system, chopping stones and dirt. “It was hard work.”

He used his guile and wits to simply stay alive and he ingeniously thought to ask the foreman if he needed help, cleaning his place, making his bed in the morning, and cleaning his boots.

“I didn’t have to chop anymore.” He wasn’t called Dave, he was called “youngan” [boy].

“He left me bread and food from the kitchen.”

As soon as he had gotten to Camp, his forearm was tattooed with 141631. He was given a haircut “with a cut in the middle, a stripe” and a striped uniform to replace his confiscated clothing. He was forced to wear an armband and a yellow Star of David and he had to step off the sidewalk and into the street when German soldiers approached him. He lived every day for five and a half years on coffee substitute, a watery spinach or similar soup, and 0.25 kg of bread, which was meant to be divided between the supper and the following breakfast. The food was not non-existent; it was calculated to starve the Jews into corpses. He weighed just 78 pounds. “I looked like a skeleton.”

He listened to “Deutschland Über Alles,” “German for the Whole World.”

They told him after 90 days he would go home. “I wasn’t going home. It was a camp.”

The infamous gateway at Auschwitz 1 concentration camp had a sign that read: 'Work makes you free'. In fact, Jews and other groups went through this gateway to their death, rather than to freedom. “You were only free when you died. That was the only way to get out of it.”

On May 5, 1945 the Americans liberated the forced labor camp and David spent the next several months recuperating in refugee camps, stopping in Canada before immigrating to the USA in 1950. “I saw the French lady saying hello to me.” The Statue of Liberty welcomed him.

He had met his future wife, Marie Roza in Paris, after the war. She labored at the concentration camp also, making clothing for the German army. “She had a beautiful voice, a soprano. I called her ‘my tchotchke’, something special.”

They have one daughter, Lydia, three grandchildren and seven great grandchildren.

He needed work when they came to America. “I’m a mechanic!” They said “The war is over.”

So he started making men’s clothing. “I just started. I didn’t know how to sew.” He only took home $26.00 a week even though he was hired at $1.00 an hour because he had to pay union dues and pay Uncle Sam. “I don’t have an Uncle Sam.” “You do now”, he was told.

That was not enough money to survive.

While living in the Bronx with his parents, he had made friends with a young boy who was now a grown man with his own interior decorating business. “Come work with me.” He started introducing David as a French interior decorator.

He opened his own store, “Dave’s French Interior Decorating” in 1952.

He even made padded cornices from wood and plywood. His late wife sold cloth in the front of the store.

“That’s chutzpah!”

Powerful in his stark simple language, David narrates his personal and poignant testimony through the “Witness to History Project” of the Holocaust Awareness Museum and Education Center, documenting the crime, perpetuating the memory and furthering the lessons about the Holocaust.

His distinct voice details his journey of suffering, tragedy, and loss. The Nazis did not act alone. They were supported and assisted by people from within the countries they occupied across Europe. Silence, apathy, and indifference are the enemies.

David also speaks to schools regarding bullying prevention strategies. “If somebody gives you trouble. Don’t say anything. Walk away. I prayed every day for five and a half years just to live until the next day. How can one bully twist the mind?”

Not much of a television aficionado, he does watch “Are you Smarter than a fifth grader”.

Well, are you? “Sometimes,” he laughed.

He never looks at the serial-number digits on his skin. It brings back too many painful memories.

“It’s hard for anyone to understand what was going on. Everyone was fighting for their life.”

He persevered despite tremendous horrors and obstacles. Never again.

“If you have life, you have hope,” said Mr. David Tuck.

David continues to exhibit optimistic spirit and milestones of heroic strength and resilience.

The Hebrew name David means "beloved". Several stories about David are told in the Old Testament, including his defeat of Goliath, a giant Philistine.

On April 10, 2009 this holocaust survivor found himself the target of a carjacker.

Witnesses congratulated Dave Tuck for the way he resisted. But why would a man his age try to thwart a much younger, stronger carjacker?

"It's the will to live," Tuck said.

As a holocaust survivor, Tuck said trying to resist his attacker was a reflex.

Recommend a Spotlight. E-mail vjmrun@yahoo.com

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Students rally to Holocaust survivor's message in Warminster

By Gary Weckselblatt Staff Writer | Posted: Thursday, November 13, 2014 3:30 pm

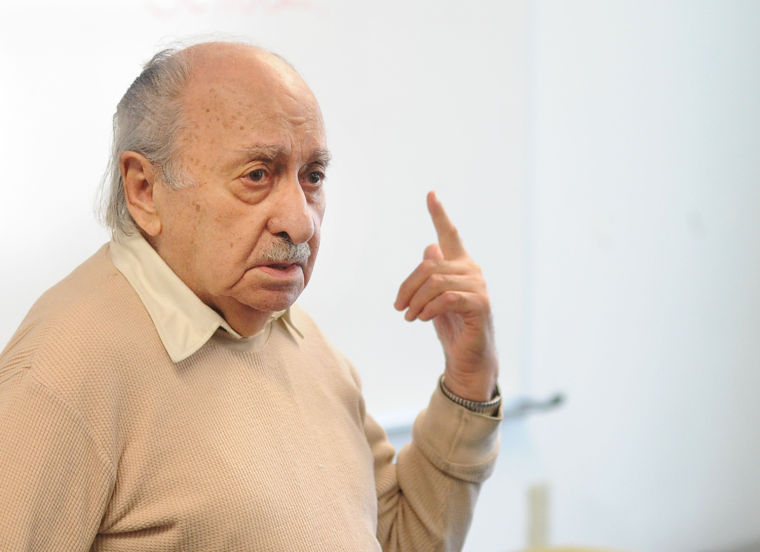

WARMINSTER, PA - NOVEMBER 14: Polish Jew David Tuck, who survived several Nazi labor camps during World War II, addresses students at Delaware Valley High School November 14, 2014 in Warminster, Pennsylvania.

(Photo by William Thomas Cain/Cain Images)

As much as the fear he lived with for 5½ years as a Jew during the Nazi Holocaust, David Tuck worries the world will forget the slaughter of 6 million Jews.

It’s why the Poland-born Tuck, who was taken at the age of 10 to the Lodz ghetto and spent time in the Posen labor camp and Auschwitz, has spent the last three decades as a piece of living history, giving first-hand accounts of his fight to survive as a young boy.

On Thursday, about 20 students at Delaware Valley High School, an alternative school in Warminster, were captivated by Tuck’s story.

They listened to an hour-long presentation that included a slide show of how the Germans began to isolate Jews beginning in 1933 and ultimately sent them to their death in concentration camps. He also showed family photos.

After nearly an hour of a question-and-answer session, most of the students surrounded the survivor to get their picture taken with him. Lisa Liberty, the school’s director, called it “a beautiful moment.”

“People deny that the Holocaust ever happened,” Tuck said. “Kids today, they live in a different world. It’s more than 60 years already. I like to talk to the kids. They learn the lesson of how people suffered.”

Tuck said he noticed the students’ appreciation.

“I’m glad they paid attention to what I was saying,” Tuck said. “They learned something for their future. Never give up. Get educated. Stay in school. You can be anybody you want to be.”

While many of the students’ questions were about the horrors of the Holocaust — How did you stay positive? What was your most traumatizing experience? — they also wanted to get a measure of the man today.

Did he ever eat a cheesesteak? “Of course,” he said. But his favorite food is fish; not sushi, though. Does he drive? He got his license driving a stick shift in the Bronx, he told them.

They asked to see the tattoo the Germans gave him — 141631 — and asked if he had others. They were told Jews couldn’t be buried in a Jewish cemetery if they had other tattoos.

Did he ever go back to Germany? He never did. “There’s nothing to see for me,” he said. “I don’t care.”

“Our students responded beautifully to his story, to his emotions,” Liberty said. “Their questions were so thought-out and pure. The questions were so valid and they were wondering how he felt today about his past.”

Throughout his talk, Tuck repeated that he “felt predestined to survive.” Each night, before he slept surrounded by others who shared his plight, he prayed: “Please God, let me see the light the next day.”

The students were in awe of his emotional strength.

“The fact that he went through all this and some people kill themselves for less important things like bullying says a lot about him,” said Daquane Stephens, a senior from Philadelphia. “And he decided ‘I’m still going to fight’ while people were dying, and other people were killing themselves. He decided ‘I’m going to keep on fighting and I won’t give up.’ “

Samantha Aravd, a senior from Levittown, said, “He made me realize how fortunate I am for the things I do have, because I don’t know what I would do without my family. He said he didn’t know how he survived. I don’t know how he did it either. If I was ever in that situation, I wouldn’t know what to do. Even though he was scared, he kept hoping that better days will come. And his better days did come. He survived.”

Tuck, who now lives in Bristol, met Marie Roza, also a camp survivor, while recuperating in Milan and Paris after the war. They moved to New York in 1950, and Tuck later started an interior decorating business. The couple had a daughter. Marie died from a stroke.

Tuck, who has three grandchildren, speaks to students as part of a Holocaust Awareness Museum and Education Center program and students write essays so he can get their perspective on his experiences.

Asked for his thoughts on those who stole his youth and left him an emaciated 78-pound mess as a teenager, Tuck said, “I will never forget, never forgive. But I don’t live with hate. If you live with hate, you’re destroying yourself.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

who’s next?’

By JD Mullane

Columnist

@jdmullane

Posted Jan 25, 2020 at 5:01 PM

“I will speak about this until I die. If we forget what happened, it will happen again,” said Dave Tuck of Levittown, who spent two years in a Nazi concentration camp.

There was music playing at Auschwitz on that August day in 1943. Dave Tuck, a Jewish teenager, thought, “It’s not going to be too bad.”

He had already spent two years in a hard labor camp, barely surviving on a twice-daily ration of a slice of bread and sips of coffee. He weighed 78 pounds.

But as he stood there, he saw German soldiers separating men from women and children.

“One way meant you were slave labor, the other meant death and the crematoriums,” said Tuck, a Holocaust survivor who lives in Levittown.

He stopped speaking. His living room was silent.

After a moment, he said, “I will speak about this until I die. If we forget what happened, it will happen again. Last time it was me. But who will be the victims next time?”

Jan. 27, 1945, is a date he recalls the way the rest of us recall our birthdays or anniversaries.

Auschwitz was liberated, the largest and most deadly camp in a web of machinery that killed Europe’s Jews on an industrialized scale in the millions. The numbers horrify.

“The Polish population, it had 34 million,” Tuck said. “Ten percent of the population was Jewish — 3,400,000. Three million two hundred thousand didn’t make it. For every 10 Jews, nine didn’t make it.”

He was 10 years old on Sept. 1, 1939, when Germany invaded his homeland of Poland. He had no idea what was coming.

“I got up, turned on the radio to listen to music, and all they kept playing was ‘Deutschland Uber Alles,” or ‘Germany Overall,’” he said.

“I lived in a town where there were only 18 Jewish families. They gave us to wear a yellow armband, on the left arm. Then they gave us a Star of David, one on the front, one on the back,” he said.

The invasion started World War II. His mother had died when he was 6 months old. His father had left him. Tuck was raised by his orthodox grandparents in Jarocin, a small town on the German border.

When the Nazis arrived, he was sent to the Lodz ghetto, where he spent a year. Then to Posen, a labor camp in Poland, where he lied about his age, saying he was 15.

“Why did I say 15? Because at 10, I have no right to live. At 15, I could work,” he said.

He gave out ration cards in an office. He received twice-daily rations of a slice of bread and sips of coffee.

“That was it,” he said.

He was reassigned to collect trash. He was ordered to round up 10 boys to help. Starving, three of them ran away, knocking on doors seeking food. They were caught. In a soccer stadium, the Nazis built three gallows, each with a chair.

“They brought those three boys in and put them in chairs, put the noose around their neck. And the stadium is full with civilians,” he said.

The gallows opened, and the three boys dropped through, still seated on the chairs.

“The SS man, he turns around and says, ‘They didn’t obey orders. If you don’t obey orders, this is what happens to you.’ I still can see it.”

In August 1943, he was sent to Auschwitz, where those chosen as labor were tattooed with a number, since tattoos made it easier for the Germans to identify corpses.

“I still have a number from Auschwitz,” Tuck said. “I don’t know if people know about it -- only Auschwitz gave tattoos. Only Auschwitz gave the blue-and-white outfit. No other.”

He rolled up his sleeve and showed me the number on his left forearm: 141631.

From there he was sent to an Auschwitz sub-camp, Eintrachthutte, where he built anti-aircraft guns. Then he was sent to Mauthausen in Austria, then to Guzen II, an underground factory where the Germans built Stuka aircraft.

All that time, there were no newspapers or radios.

“I didn’t even know what was going on in the world,” he said.

He thought he would die of starvation.

“Every morning, every night, I went to sleep, I’d say, ‘Please, God, let me see the light the next day.’ I thought every day was the last day,” he said.

On May 5, 1945, American soldiers liberated Gusen II.

“I was 15 years old and weighed 78 pounds,” he said.

After the war, he met his future wife, Marie, also a Holocaust survivor.

They went to Italy, then to France, then to Germany, where they married. In 1950 they immigrated to the U.S.

He made his living at a men’s clothing factory, then on his own selling interior decor, first in Brooklyn, then in Burlington. He later moved his business to Feasterville in Bucks County.

He didn’t speak about his experiences during the Holocaust until 1979. In that time, he estimates he has spoken to tens of thousands of schoolchildren, warning them.

“Whoever they are, they have to know that they could be next. This I will tell them until I can’t anymore. I have faith they will hear my story, and remember, and tell their kids, too,” he said.

Columnist JD Mullane can be reached at 215-949-5745 or at jmullane@couriertimes.com.

David sitting with his grandparents,

Sybil and Jehuda

David's parents, Pola and Morris

click on thumbnail

to enlarge